The Mau Mau uprising (1952-1960) presented an existential threat to British colonial rule. The colonial government’s response was brutal and multifaceted: military operations, detention camps, and villagization. But perhaps one of the most insidious strategies was economic warfare. A special tax was imposed solely on the residents of the so-called “emergency areas”—primarily the Meru, Kikuyu and Embu communities, collectively referred to as the people of Múríma. The official justification was the need to fund the “maintenance of law and order,”—forcing these communities to pay for their own oppression.

In reality, this tax had a far more sinister objective:

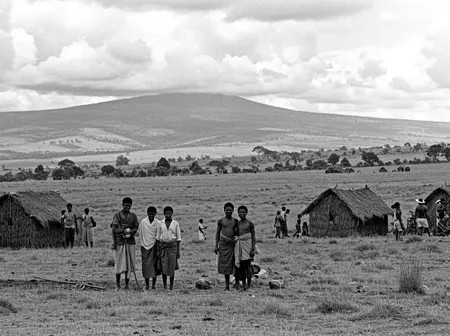

To understand the tax’s impact, we must recall the economic context of 1950s Kenya. Many communities across the country were still operating within subsistence or barter economies. Money, while present, was not the absolute necessity it is today.

The special tax changed that overnight for Meru, Kikuyu and Embu families. They had to find cash. This urgent need triggered a massive societal shift:

This was not a voluntary entry into modernity. It was a desperate adaptation for survival under extreme duress.

The cruel irony of the colonial policy is that it ultimately produced the opposite of its intended long-term effect. While designed to impoverish and suppress, it accidentally provided the communities of Múríma with a significant head start in the new monetary economy.

By the time Kenya gained independence in 1963, these communities were already:

When independence arrived and opportunities in land ownership (through land-buying companies), commerce, and civil service opened up, the Meru, Kikuyu, and Embu were, by circumstance, better positioned to take advantage of them. Their economic prominence was not a result of privilege, but rather a consequence of their forced and painful early immersion into a capitalist system.

This economic head start did not go unnoticed. Other communities, who had not been subjected to the same brutal economic forcing mechanism, observed the relative advancement of Central Kenya. From this observation, a dangerous and simplistic narrative was born: that the Meru, Kikuyu and Embu were “dominating” the economy, often framed as an unfair advantage rather than a historical consequence.

Tragically, the post-colonial state did little to correct this narrative. In fact, it often perpetuated the same strategy of isolation under new guises:

The scheme to isolate Múríma, hatched in colonial offices, found a new lease on life in independent Kenya’s political playbook.

The story of the special tax on the Meru, Kikuyu and Embu is not a claim to superior sacrifice. Every community in Kenya contributed to independence in its own way. Nor is it a justification for present-day economic disparities.

It is, however, a crucial piece of historical truth. It explains a part of Kenya’s complex economic puzzle that is willfully ignored. Acknowledging this history allows us to:

The communities of Meru, Kikuyu and Embu paid a heavy, forgotten tax for Kenya’s freedom. That payment was not just in blood and lives, but in a forced economic transformation that continues to define the nation. It’s time we remembered, acknowledged, and learned from this forgotten chapter.

Leave a Reply