Nairobi, Kenya: The promise of a better life overseas is what first lured Mary Muroki into the trap. Like thousands of Kenyans each year, the 54-year-old had spent months searching for international work opportunities, her applications disappearing into the void of unanswered emails.

So when a trusted friend mentioned a housekeeping job in Johannesburg, it felt like divine intervention. “I thought my struggles were finally over,” she recalls, her voice tinged with the melancholy of hindsight.

What followed was not the bright future she imagined, but five years of systematic abuse that laid bare the brutal mechanics of human trafficking. Her story—one of survival against impossible odds—offers a window into a global crisis that ensnares millions while exposing the sophisticated tactics traffickers now employ across Africa and beyond.

Mary’s journey from hopeful jobseeker to enslaved domestic worker began with the ordinary rituals of migration: medical checks, signed contracts, a one-way ticket to South Africa. The veneer of professionalism dissolved the moment she arrived.

“The driver took me straight to a private home, not the hotel I’d been told about,” she says. “That’s when I first felt afraid.”

The abuse started almost immediately—small cruelties designed to test her compliance. Racist slurs over imperfectly ironed shirts. Threats when meals weren’t prepared exactly to taste. Then came the violence: slaps for dust left on furniture, kicks for bathroom breaks deemed too long. “They treated me like a malfunctioning appliance,” Mary recounts. “Something to beat into working order.”

Worst of all were the broken promises about wages. “Every payday brought excuses—the bank was closed, the money would come next week.” When she dared to protest, her employers brandished her confiscated passport like a weapon. “They’d say, ‘Who will believe an illegal immigrant?’”

Mary’s story goes beyond the suffering she endured, and is a testimony of how she outmaneuvered her captors. She developed what psychologists call “trafficking survival strategies”—subtle acts of resistance that kept her alive.

She learned to mute her reactions to provocations. “If I cried, they hit harder. If I stayed silent, they lost interest.” She negotiated “promotions”—first from cleaning to cooking, then to caring for the family’s aggressive Boerboel dogs. “Walking those monsters gave me precious minutes outside the house,” she says.

Most crucially, she noticed everything: the guards’ shift patterns, which neighbors might offer help, even which tree branches could bear her weight during an escape.

This quiet observation led to her salvation. During dog walks at a nearby mall, she caught the attention of shop workers who noticed her bruises and hollow-eyed exhaustion.

“They would greet me, ask about my day and marvel at how I was able to walk around with such big dogs on my own,” Mary says. “Small kindnesses that told me I wasn’t invisible.”

Her breakout, when it finally came, was both cinematic and terrifyingly mundane. One moonless night, after confirming her employers were asleep, she scaled a backyard mango tree, dropped onto the street, and ran.

“The dogs didn’t bark—they knew my scent,” she marvels. The sympathetic security staff at the mall helped her get to the police station. But freedom nearly eluded her at the last moment.

“The police almost turned me away at the station,” she admits. “They assumed I was another undocumented migrant causing trouble.” Only when she produced a tattered copy of her original contract—kept hidden in her bra for years—did officers take her seriously.

Even then, bureaucratic inertia nearly sent her back. “It took three days just to confirm my identity with the Kenyan embassy.”

Mary was repatriated to Kenya five days after her dramatic escape.

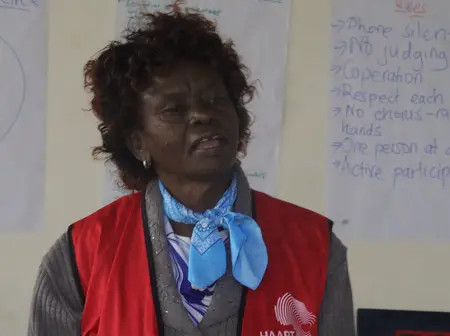

On returning to Kenya, she received counselling and support from Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART) Kenya, a non-governmental organization dedicated to eradicating human trafficking in Eastern Africa.

Mary’s ordeal reflects alarming regional trends. According to the UN’s 2023 Global Slavery Index, Africa hosts 7.1 million modern slavery victims—nearly 15% of the global total. The International Organization for Migration reports that 12% of trafficking victims in East Africa are children, many forced into mining or commercial sex work.

During the national commemoration of the World Day Against Trafficking held on July 30, 2025, State Department, Carren Ageng’o, Principal Secretary (PS) for the State Department for Children Services, rallied Kenyans to confront this grievous crime.

“Human trafficking thrives on deception and exploitation, luring victims with false promises of greener pastures only to trap them in modern slavery. Together, let us recognize that trafficking in persons is organized crime and end the exploitation,” she declared.

She highlighted reported key progress against trafficking under the Counter Trafficking in Persons Act, 2010. Achievements include rescuing 153 Kenyans from forced scamming in Myanmar, training over 700 law enforcement and aviation responders, supporting 35 survivors with business grants, and establishing a shelter for 20 victims.

The Counter Trafficking Secretariat has also highlighted varied trafficking forms like child labour, forced begging, organ harvesting, and child radicalisation. These reflect trafficking’s complex causes, including poverty, unemployment, family breakdown, conflict, and climate displacement.

PS Ageng’o praised survivors’ resilience, stating, “Their voices are a powerful weapon in raising awareness and preventing others from falling victim.”

She said the state was focused on early detection, reporting, and prevention of trafficking, and urged the public to report suspicions to the National Crime Research Centre or the Secretariat. The PS reaffirmed its dedication to victim protection and prosecution of perpetrators, calling for united efforts to eradicate human trafficking nationwide.

On July 25, 2025, HAART Kenya and Kenya Airways (KQ) announced a historic partnership to provide discounted flights for human trafficking survivors returning from Southeast Asia to East Africa.

The agreement, signed at the KQ Headquarters in Nairobi, marks a global first in the airline industry. It aims to ensure survivors can return home safely, affordably, and with dignity—key in the fight against human trafficking.

Jennifer Njuguna, Kenya Airways’ Commercial Manager, declared, “To the survivors, we see you, we stand with you, and we are committed to bringing you home.”

Human trafficking remains a global crisis affecting millions, including thousands of Kenyans annually. In 2025, 153 Kenyans were rescued from trafficking in Myanmar; 27 repatriated on February 22, 48 on March 22, and 78 on April 5. Yet many remain trapped.

The new partnership offers a vital lifeline, allowing survivors to reunite with families and begin healing. The agreement builds on Kenya Airways’ 2023 Trafficking in Persons Policy and HAART’s victim-centred approach, setting a new benchmark for compassionate repatriation.

Tabitha Njoroge, HAART Kenya’s CEO, said, “This partnership is a statement of values, affirming our shared commitment to a victim-centred, trauma-informed approach.” As the World Day Against Trafficking in Persons nears, themed “Human Trafficking is an Organised Crime: End the Exploitation,” the collaboration exemplifies the UN’s Four P’s Strategy—Prevention, Protection, Prosecution, and Partnership—highlighting cross-sector cooperation in ending exploitation.

While Kenya has taken steps to combat the menace, many of the agents that dupe citizens into slavery disguised as employment are yet to face justice. HAART collaborates with law enforcement and local authorities to assist survivors.

“We refer cases to the police and DCI, and help survivors to follow up the proceedings, but legal processes are slow, and there isn’t much we can do to change this,” Haart Program Officer Allan Sirima admits.

According to Sirima, the HAART also provides shelter, psychotherapy, and limited economic empowerment programs.

“We help survivors rebuild their lives through training and small business grants,” he adds.

Life is slowly going back to normal for Mary, who is 55. She has opened a small business and is busy picking up the shattered pieces of what was a relatively peaceful existence before the fateful flight to Johannesburg.

She has also joined the HAART advocacy team to ensure that as many people as possible learn about the dangers of getting trafficked.

“I am a committed anti-human trafficking advocate because I do not wish anyone else to experience the horrors I went through in South Africa,” she says.

Leave a Reply