How the current Kenyan government is transforming the whole sports ecosystem in the country following the recent CHAN 2024 success.

Say whatever you want about the current Kenyan government, but compared to previous regimes, they deserve their flowers for the renewed investment in sports—something this country has not witnessed for at least two generations.

Before William Ruto took the oath of office in 2022 as Kenya’s Fifth President, sports investment was already a key pillar of his Kenya Kwanza manifesto.

Recognising the chronic underfunding of the sector, his coalition promised bold reforms: a high-level task force to unlock sustainable financing, with options ranging from a national lottery and tax incentives for sponsors, to ring-fenced levies and public–private partnerships for infrastructure.

The vision was simple but ambitious: end the cycle of stalled projects, bring Kenyan facilities up to international standards, and protect them from the land-grabbing menace that has crippled progress in the past.

At the grassroots, the manifesto sought to transform talent identification. The plan was to expand the National Youth Talent Academy into every county, covering all sporting disciplines beyond the usual athletics and football.

Kenya Kwanza also pledged to nurture champions through County Sports Talent Academies, inter-county leagues, and systematic scouting programs.

Alongside this came recognition of the creative economy as a growth frontier, with promises to enforce copyright, invest in digital infrastructure, and help musicians, artists, and actors monetize their craft.

The agenda tied these commitments to a broader youth empowerment drive, promising a stand-alone Ministry of Youth Affairs, Arts and Sports.

This was framed not just as cultural enrichment but also as an economic imperative: offering young people opportunities, retired athletes dignity through a benevolent fund, and positioning sports tourism as a gateway for Kenya to host major international events. In short, sports and the arts were to be recast as engines of job creation, national pride, and global competitiveness.

So, three years into Ruto’s tenure, how much of this agenda has already been fulfilled?

Ruto’s first appointment to the newly-structured ministry was Ababu Namwamba, a familiar face who had once held the same docket under the Mwai Kibaki–Raila Odinga coalition in 2012.

Back then, Namwamba oversaw the enactment of the Sports Act under the 2010 Constitution—a landmark piece of legislation that introduced accountability, streamlined governance, and created institutions like Sports Kenya, the Kenya Academy of Sports, and the National Sports Fund.

The Act also established the Sports Disputes Tribunal, enforced athlete rights, introduced anti-doping measures, and mandated financial transparency to professionalize the sector.

Namwamba’s return saw the launch of the Talanta Hela programme, aimed at unearthing talent through nationwide grassroots tournaments and school competitions.

For the first time in years, the Kenya Secondary School Sports Association (KSSSA) games were broadcast live on KBC in 2023.

From those games, talents like Aldrine Kibet and Amos Wanjala were discovered, securing moves to Spain’s Nastic Soccer Academy. Others, like William Gitama Mwangi and Austin Odongo, would shine in international tournaments such as the Gaúda Cup.

The programme’s impact was historic. It birthed the Kenya U17 girls’ team Junior Starlets that qualified for the World Cup—the first Kenyan side ever to reach a world tournament at any level.

It also helped assemble a U18 boys’ team that reached the CECAFA finals, and laid the foundation for the U20 squad that went on to qualify for the 2025 Africa Cup of Nations in Egypt for the first time in history.

Namwamba also negotiated the lifting of a FIFA ban on Kenya, gave football extensive government support (including free-to-air FKF Premier League broadcasts), and played a role in shoring up rugby and athletics.

Notably, Kenya avoided a World Athletics ban over doping after his ministry secured $5 million in anti-doping funding to last until 2027.

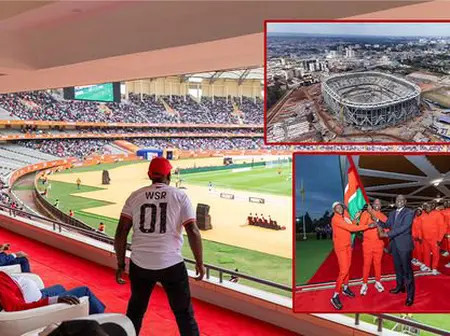

Most importantly, under Namwamba, Kenya—together with Tanzania and Uganda—won hosting rights for CHAN 2024 and AFCON 2027, prompting the urgent renovation of Kasarani and Nyayo stadiums and inspiring the blueprint for a brand-new 60,000-seater: Talanta Sports City, the first major arena built since Kasarani in 1987.

FIFA president Gianni Infantino leaves Talanta Stadium in Nairobi which is currently being constructed in preparation for AFCON 2027. The Italian will be at Kasarani Stadium to witness the #TotalEnergiesCHAN2024 final between Morocco and Madagascar later today. pic.twitter.com/kJTYXhNaYM

But politics intervened. The 2024 Gen Z protests forced Ruto to dissolve his cabinet, with Namwamba among the casualties. He was briefly replaced by Kipchumba Murkomen before Salim Mvurya took over the ministry in early 2025.

Under Mvurya, the headline focus has been infrastructure. Kasarani and Nyayo were upgraded to host CHAN 2024 matches, while the Talanta Sports City—being built under a public–private partnership with China Road and Bridge Corporation—is on track for completion before AFCON 2027.

Though athletics still struggles with lack of tartan tracks, the government has pledged to correct this as part of wider renovations.

Following Harambee Stars’ run to the quarterfinals of CHAN 2024, President Ruto doubled down on his vision, pledging 30 new stadiums by AFCON 2027.

“We are building facilities that will serve athletes and communities alike for generations,” he declared during a luncheon with Harambee Stars players at State House on August 28, committing to additional stadiums across the country.

Rewards like the KSh 5 million payouts to Harambee Stars players at CHAN 2024 showed a marked improvement from the meager allowances of past years. But the question lingers—where is the money coming from?

Kenya Kwanza’s manifesto promised a National Lottery to fund sports and the arts sustainably. Ruto has since formed a task force and set up a National Lottery Board, but the project is still in its infancy, with enabling laws yet to pass.

For now, funding continues to come from Treasury allocations and betting industry levies.

This has not stopped public perception from linking recent windfalls, like the Harambee Stars rewards, to lottery proceeds. In truth, those millions came directly from government coffers.

The National Lottery remains a promise in progress—but one that, if realized, could permanently reshape Kenya’s sporting ecosystem.

Financial Incentives For National Sports Heroes, Better Federation Governance & The Next Chapter

The government has also moved to put financial incentives at the heart of its sporting policy. On a recent appearance on Sporty FM, Sports Permanent Secretary Elijah Mwangi pledged that the bonus scheme rolled out for Harambee Stars would be extended across disciplines.

This was witnessed in June after Faith Kipyegon and Beatrice Chebet were each awarded 5 million shillings each for breaking world records in the 1500 and 5000 meter events at the Oregon Diamond League classic respectively.

“Some used to say that we give promises but don’t deliver. In sports, when we give a promise, we deliver,” Mwangi said. “We have reviewed our scheme, and everybody who breaks a record — whether in marathon, judo or taekwondo — will receive five million shillings.

“ If you go abroad and break a record, it’s five million. That is constant, it’s in law, and it has been approved by the relevant government agencies. We already have reserves for that. The same way we rewarded our boys, we will reward others.

“If you participate in the Olympics and win gold, you will get three million shillings. Silver comes with two million, and bronze with one million.”

Mwangi added that Kenya’s new national sports policy, drafted in 2025 and headed for Cabinet and Parliament approval, would transform the sector further. “This new policy revitalizes sports — it will take care of athletes in retirement, address their health, and strengthen the governance of our federations.”

Still, he admitted that governance remains the sector’s biggest test. The government already covers key costs for athletes — from travel and accommodation to allowances and cash rewards — but it cannot sustainably carry every athlete alone. This is why federations are being urged to open their doors to private investment.

“For private investors to come on board, there must be guarantees that money will be managed prudently and accountably — and that’s why we cannot run away from good governance,” Mwangi explained.

While most federations are compliant, a few continue to fall short. The Sports Registrar has the authority to sanction or even deregister those that fail to meet required standards.

Recently, the ministry convened a meeting at Kasarani that brought together 143 federations to chart a way forward on governance reforms, transparency, and investor confidence.

William Ruto’s administration has undeniably injected new energy into Kenya’s sporting landscape.

From the renovation of Kasarani and Nyayo, to the construction of the ambitious Talanta Sports City, to the Sh1.7 billion earmarked for grassroots academies, the government has shown a seriousness about sports that has been missing for decades.

Private sector partnerships, like those seen in the Safari Rally and through the new technical committee on sponsorships, are beginning to ease the state’s financial burden, while a revamped rewards scheme for athletes has set a new benchmark for recognition.

But challenges remain. A recent Sh3 billion cut to the Sports, Arts and Social Development Fund underscores the tension between lofty ambitions and fiscal realities.

Major projects like Talanta City rely heavily on public–private partnerships whose details remain opaque, while long-stalled stadiums across the country continue to draw public frustration.

And for all the progress in policy and infrastructure, governance in sports federations remains fragile — the weakest link in a sector now poised for unprecedented growth.

Beyond government initiatives, there are also legislative efforts aimed at reshaping how sports are funded and governed. In 2024, Nairobi Senator Edwin Sifuna tabled amendments to the Sports Act that would require county governments to allocate at least one percent of their revenue to a County Sports Associations Fund.

The money, managed by county sports officers, would go directly to registered associations under the Act and be supplemented by grants or donations from other sources.

Sifuna argues that this reform would reduce over-reliance on donors and sponsors, which has stifled consistent talent development, while also strengthening the financial independence of federations.

Sifuna also proposed for sports organizations in Kenya to register as companies, enabling them to attract investors, sponsorships, and equity in the same way commercial enterprises do.

“We had proposed amendments to the Sports Act that would allow sports organizations to register differently—as companies,” Sifuna said speaking during the Creative Economic Forum between Kenya and the USA in June.

“That way, for example, someone could say Nairobi City Thunder is owned by shareholders. You could buy shares, bring in sponsors, attract equity, and grow the sporting organization. Unfortunately, that amendment was shot down in the National Assembly.”

Debate continues over whether the fund should cover infrastructure projects such as stadiums and training facilities, with some lawmakers cautioning that the allocations may not be sufficient to sustain such capital-intensive developments.

If the government can marry its ambitious infrastructure projects with genuine accountability, sustainable financing, and stronger federation leadership, then Ruto’s promise to make sports a central pillar of national pride and economic opportunity might finally be realised.

Leave a Reply